WARNING: THIS ARTICLE CONTAINS SPOILERS

The Bengal language Indian director Satyajit Ray once stated “It is only in a drastic simplification of the style and content that hope for the Indian cinema resides. At present, it would appear that nearly all the prevailing practices go against such simplification”.

Pather Panchali (1955), would be the first instalment of the impromptu Apu Trilogy, perhaps the most celebrated of Indian cinema. Ray himself would become an internationally renowned auteur, the face of the Parallel Cinema, with legendary filmmakers Ritwik Ghatak (1960’s Meghe Dhaka Tara starring Supriya Devi, his films are meticulous depictions of feminism and partition) and Mrinal Sen (the great 1976 Mrigayaa starring the Bollywood star and former member of the Parliament, Rajya Sabha, Mithun Chakraborty) amongst his company. He’d gain the admiration of filmmakers Kurosawa, John Huston (who saw the rough cut and brought the film to the attention of the MoMa international film curation), and the filmmaker Ray would’ve identified himself the most with, Jean Renoir (who’d emphasise to Ray during their first ever encounter the importance of the ‘details’ captured in film).

.

Cryptic narratives

Panchali was Ray’s first film, and it is also the first film most of the crew members had ever worked on (including cinematographer, Subrata Mitra). Production lasted several years, Ray pawned his wife’s jewelry, sold his insurance, and eventually the West Bengal government would pay for several expenses. What Panchali did as a film for the time it was released was spark a spotlight for India in terms of a marketable cinema and a country branding the face of a filmmaker who coined the birth of a singular movement, the Parallel cinema (his earlier films are similar to the films of the Neo-realists). Like a professor, Ray would carefully articulate to producers all three of his Apu films with storyboards as no one either understood or empathised with his notions on the narrative structure.

The Indian director believed conventional narratives formalised even by great films come to be dated at some given point because what creates the illusion of reality far greater are those irrelevant details Renoir advised him on. The details which fill those imperceptible gaps between those classical, more older Hindi-language pictures (examples being Franz Osten’s Prem Kahani and V. Shantaram’s Kunku, both from 1937) and the marketable stardom of Zubeida and Durgabai Kamat. He was more interested in taking the unhurried approach to his material which has been given the case with the prolonged muteness of subtlety and performance from professionals and non-professionals that distinguished his work, and pretty much seemed consistent throughout his career (his later films, beginning in 1970 with The Adversary, have a much more political tenor, which is more or so bluntly shown from his 1977 film The Chess Players).

.

Bengali triptych

The trilogy, centred on the Ray family, as a whole, feels more temperamental than the films do as standalones. Pather Panchali is perhaps colder while Aparajito (1956)lingers on the weighing tragedy from its very beginning. As a sequel, it is more of a technical improvement, too. It is a more focused and tighter film, and Ray finds the right balance between the precise exploration of setting and mood while evolving the relationship of Apu, and his mother, Sarbojaya. Though not a story originally conceived by Ray (Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay wrote the first two original novels of the same title, Ray wrote the original screenplay for The World of Apu, 1959), the life of Apu and his family seems so evidently close to his personal memoir. He has often considered himself a dry filmmaker, and a very still observer of the happening and the human expression. Thematically, his earlier films hold a candle to Vittorio De Sica, while in artistry, his films feel inspired by Renoir and perhaps even encouraging for the New Wave filmmaker Jacques Rivette.

The trilogy features a score by the Bengali musician and Hindustani classical composer Ravi Shankar (Sitar Maestro), a score improvised during the makings of Panchali and intrinsically engrossed by the unfoldings of Apu’s subdued growth from boy to man. The collaborations Ray had with the finer elements of his trilogy should be studied by the newer generation of filmmakers; though, it wouldn’t be surprising to learn his methods and beliefs wouldn’t necessarily attract the modern filmmaker so prone to an impatience derived on achieving aesthetics and maundering vision.

There’s an insightful interview he has with George Stevens Jr (director of the American Film Institute from 1967 until 1980) in which he describes his changing relationship with music. He speaks upon his collaboration with Shankar, and his attempt at getting Shankar to create a musical piece in under three minutes. For Ray, it proved Shankar was not a professional film scorist because he could not apply to such a limitation he was never used to as a musician. Quite a viewpoint on film scores and music really, as Ray believed music only intervenes the greater meaning of the visual story, and no movie can truly compare to the singular distinction and intention of the song. He speaks gracefully on the trial and error of making films in Calcutta for instance, such as the power outage that would periodically occur three times a day. So he can be shooting the film, or he can be editing the film, or even worse, the labs could be in the middle of processing the film!

.

Dirty experimentations

Perhaps the modern cinephile can appreciate the experiments behind Ray’s differing methods between performers and solidifying low budgetary productions. He and cinematographer Subrata Mitra technically originated the bounced lighting technique with cloth and nets (black clothed frames) to enhance the shadows and schemes of black and white film. His name is amongst the filmmakers Kurosawa, Rossellini, Fellini and Ozu. Ozu and Ray were contemporaries of similar merits and certainty given their pace, imagery, and empowering affect for the placidity.

A trilogy was never intended, though Panchali’s international success (it premiered with a Special Honours at Cannes) inspired the continuation of this saga with Aparajito. Following the Ray family, though without the elderly Indir Thakrun (Chunibala Devi), in the city of Varanasi, Apu shares a greater amount of perspective this time around. The presence of Varanasi is just one of the few broader changes for the Ray family, a village perhaps just more modernly fitted of its rurality in comparison to the Bengal village they originated from. There’s a particular visual emphasis for stairs, with Panchali, roads were a frequent emphasis for a significance defining every member of the family’s wonderment of place and a future, while for Apu, the roads played an obvious token for the unknown (the title Pather Panchali means ‘song of the little road’). The stairs are mostly seen whenever the focus is solely on Apu, such as the moments when he’s walking up the stairs on the bank of the Ganges, or the staircases from Apu’s college.

.

Departure time

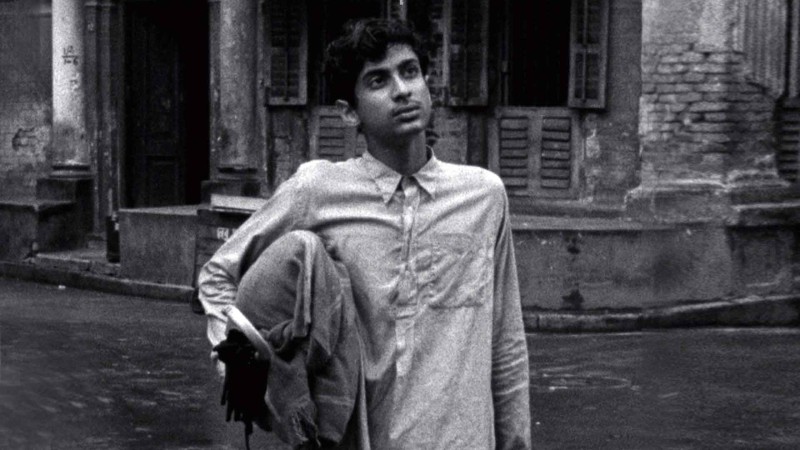

This visual transition from boy to young adult is practically the message, here, and the beautiful cinematography from Subrata Mitra is more precise and complex in conveying a blend of slight marvel and a melancholy lurking within the distance of Apu and his family. Harihar Ray (Kanu Bannerjee), the father and impoverished priest who left the village to search for work was the protagonist of the first film. He falls ill and dies within the first act of Aparajito and leaves both Sarbajaya (Karuna Bannerjee) and Apu (Pinaki Sengupta as child Apu) at a loss for security and the prospects for what’s to come. During most of the film we follow both Sarbajaya and Apu, either when they’re together or in their own isolation. For Sabajaya, she lives at home and is pretty much there through most of her life while emotionally distraught by the guilt for leaving her village, and slowly losing her son.

At one point, Sarbajaya is told that in order to achieve salvation, she must bathe in the Gange, though she never does. For Apu, he grows older (Smaran Ghosal, older Apu), coming to his own, and realising there is perhaps a chance for a more exciting life beyond Varanasi, which is practically the same sentiment Harihar had finally realised for himself when deciding to embark for something beyond the rural normality he and the generations behind him were so accustomed to. The dissension of Aparajito comes from Apu’s oblivious but meddlesome and ambitious understanding in relation to his mother. The differences between their thinking is practically a timely anecdote of an older generation restraining the present generation’s attempt at expanding the principles of an unprecedented way of life.

Despite the obvious cultural significance for viewers, Apu’s underlying thought and desire comes from the humanisation of the children forming onto their own, a part of our own civilisation that will forever be contended. He wishes to study in school instead of following his father’s footsteps to becoming a priest. Their views have been moulded differently through the conditions they’ve lived their entire lives. For Sabajaya, ambition only exists for those in the condition of chance and promise, in a given world in which the conversation and visualisation of ambition is openly interpreted by accessible instruments and necessities for moving forward. To put it simply, after the loss of Indir Thakrun and Harihar, there is nothing else for Sabajaya’s contentment, she has given what she believed was part of her duty as a wife, a mother, and a woman in the shallows of the unreachable. And for what, exactly?

The film is haunting during the phase of Apu studying away in Calcutta while Sabajaya deals with an emotional turmoil. She loses sleep and eventually loses a sense of even being. The performance from Karuna Bannerjee is incredibly nuanced, she is often quiet at the centre of Aparajito and the progression from her grace to being helplessly timorous is ghostly. It’s been said by viewers of the trilogy that Pather Panchali is the better film, though it is probably unfair to even compare any of the three.

Aparajito is a clearer distinction for how families drift apart. It comments on that relatable tethering thought many children end up having heading into their adulthood, the thought of staying home and being around your parents in a perpetual state of mind and presence is a burden. And while it strikes such a transparent sentiment for the sons and daughters of the world, Ray counters this with a powerful contention for the mothers of the world. The film never speaks of it, except as the viewer, we wonder through almost the entire film what exactly is the point of living a structured life? Obviously this is dependent on a culture, or the means of expectation given the conditions of which one chooses to bear a child.

.

Redemption in death

Apu, for himself, decided there was more to take from life than just simply accept. The core of the film is within Sabajaya’s unwillingness to accept this transition as she could not identify with it, ultimately leading to her emotive death. Her death is more of relief than it is a tragedy, however. It is a relief for Apu to continue forth without having to look back. For it to be a tragedy, it would have to diminish whatever plan Apu has given himself for a future. There are some beautiful moments in the sprawl of this life and death. Particularly one of the final moments of the film in which Apu purposely misses his train to Calcutta in order to spend one extra night with Sabajaya. He simply lies beside her with his eyes closed as she watches over him with a muted excitement. The ending of Aparajito is a necessary one, Apu’s journey from a studious young adult to a man must continue forth (as the final frame suggests with an open road). Harihar and Sabajaya’s stories were the central part of both Panchali and Aparajito, guiding Apu along the way as not presenters of what’s to be expected in life, but as individuals who sought an inevitable desire for something greater that would translate to the son who’d achieve it.

Stream Aparajito right here.

All the stills on this article are from Aparajito.