I’m a teacher. Last year, when I was developing my course Media and Cultural Studies, the canon of films my students watched have been timely reminders of political dissent and social strife – from The Battle of Algiers (Gillo Ponecorvo, 1966) to Do the Right Thing (Spike Lee, 1989). Yet the film that rounds up the most discussions and debate from my students is finally restored in glorious 4K, Matthieu Kassovitz’s La Haine. 25 years ago, the story of three friends of different racial backgrounds living in the desolate banlieue – the suburbs outside of Paris – exploded at the Cannes Film Festival like a powder keg. The French police, who acted as security for the festival, turned their backs towards the screen as they didn’t want the police force to be denigrated in the film based on the race-related crimes of the past. However, the past is inescapable in this dirty masterpiece.

As I write this, racial tensions have reached fever pitch this summer when 17-year-old Kyle Rittenhouse killed three protesters in Kenosha, Wisconsin, the birthplace of Orson Welles. Like Welles apathetically complex Charles Foster Kane, Donald Trump has shown little sympathy for those protesting the systemic police brutality as exemplified in his race-baiting vitriol since being dubbed as President of the United States. Like the United States, France has had a history of race-related crimes between the police and people of colour.

Malik Oussekine, a 22-year-old college student, was beaten to death by police during the December 1986 riots at the Sorbonne university of Paris as students citywide were protesting the new conservative education reform laws passed by the conservative government. In 1993, when a 17-year-old Zairian named Makomé M’Bowole was arrested along with two friends for stealing cigarettes from a local convenience store, all three were interrogated at the Grandes–Carrières police station. Eventually, two of the three suspects were free to go since they were minors. M’Bowole was not set free as Detective Constable Pascal Compain ignored the order to release him and shot him point-blank in the interrogation room. For Americans, their names could have been George Floyd or the 790 others killed by the police in the last three years.

It was these two events that inspired actor/director Matthieu Kassovitz to direct his first film, La Haine. Set over the course of 24 hours, Vinz (Vincent Cassell), Saïd (Saïd Taghmaoui), and Hubert (Hubert Koundé) find a gun after a riot, sparked by the beating and arrest of one of their friends, leading them through a freewheeling and reflective journey from the banlieue to Paris. With visual nods to Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing and the improvisational dialogue reminiscent of Martin Scorsese’s Mean Streets (1973), La Haine is a poignant, funny, and tragically prophetic look at how hate begets hate. With a restored soundtrack of music from the Beastie Boys, Isaac Hayes, and Bob Marley, La Haine pulsates at a beat and energy that is all-encompassing like the classic boom shot of the camera flying over the banlieue to the sounds of Cut Killer.

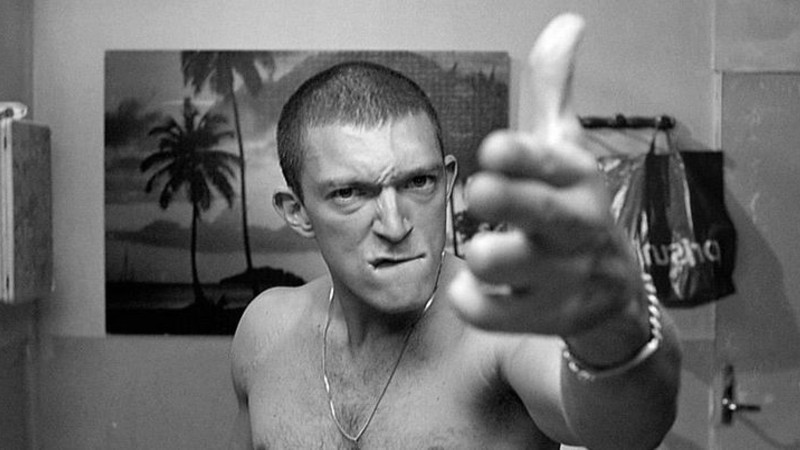

At the forefront of the film is the raw performances by the three leads. Long before his international renown for his roles in Eastern Promises or Black Swan, Vincent Cassel burst on the screen as the hot-headed Vinz reciting Robert De Niro’s mirror monologue from Taxi Driver (Martin Scorsese, 1976), yet Cassel comes across more as the obnoxiously reckless Johnny Boy from Mean Streets. Saïd Taghmaoui is memorable as the comedic pot dealer focused on getting his hair just right for his girlfriend. Finally, Hubert Koundé’s stoicism and piercing presence is at the heart of the film as he tries to calm Vinz from his anarchic tendencies while being subjected to daily racism.

Twenty-five years on, the film is a fresh and seething indictment on poverty, race, media sensationalism, and institutionalised racism. Unfortunately, the issues are still present but as Hubert says at the end of the film, “It’s not how you fall that matters. It’s how you land.” Suffice to say, La Haine remains a landmark of modern cinema and, hopefully, its message lands into the hands of a new generation trying to shake off the oppression of those currently in power and out of control.

The 4k restoration of La Haine is in cinemas on Friday, September 11th.