French actress Isabelle Huppert is best remembered for her role as the dysfunctional and sadistic piano teacher Erika Kohutin in The Piano Teacher (Michael Haneke/ 2001) or a tachycardiac Augustine in Eight Women (François Ozon/ 2002). In Things to Come she plays again a teacher (called Nathalie), but this time she lectures philosophy and has a very different demeanour and approach to life.

Unlike Erika, Nathalie is a respectful teacher, as well as a loving wife and mother. She does not challenge the scheme and the establishment of which she is part. In fact, she avoids confrontation at all costs. She does not adhere to a student strike, and she hardly says a word when her husband asks for a divorce because he is in love with another woman. Nathalie is mostly calm and considerate, a far cry from cry from Huppert’s explosive roles for which she is best known.

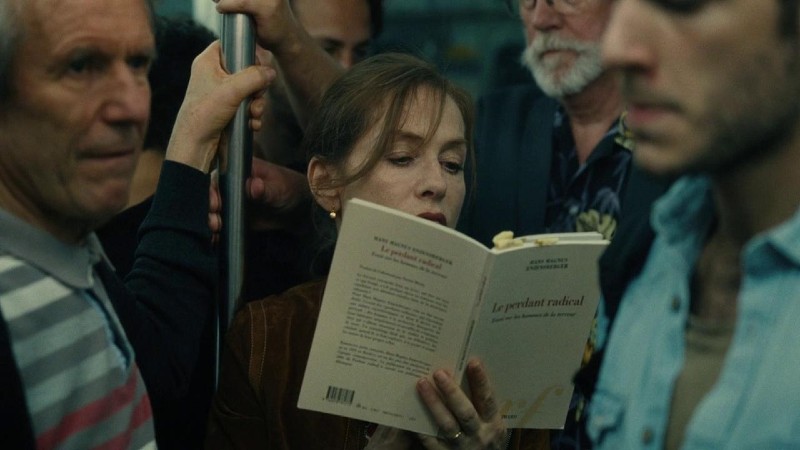

Nathalie is oblivious to the fact that she does not practise what she preaches at university. Philosophy is a venting outlet for many of her students, and many are ardent strikers and aspiring revolutionaries with radical ideas. She criticises their “radicalism” and preaches a more moderate approach to life. Her philosophy teachings seem to imprison rather than liberate her.

Her passivity towards her predicament and her latent anguish gradually choke her. She claims that she is free after her husband left her, her kids grew and her mother died, but she is unable to live out these sentiments of liberty. She points out that her black cat will not survive more than five minutes because it never knew freedom, when it escapes into the forest. She fails to realise that this is a comment on the unfeasibility of her own freedom.

Things to Come often remind viewers that death is the only inevitability of life. The film title is introduced with a graveyard in the background, and Nathalie’s mother dies of depression after being placed in an old’s people home. During funeral arrangements, Nathalie explains that her mother felt abandoned throughout her life because her parents left her as a young child. Once again, Nathalie fails to see the writing on the wall, despite her profound philosophical knowledge: her mother died because she could not handle being once again abandoned, this time by her own daughter (who put her in the old people’s home).

Various political themes and philosophical aspirations are also touched upon in the film. They include the student revolution of 1968, the lowering of the retirement age in France, the meaning of established truth, writings by Rousseau, etc. European intellectuals are mentioned throughout the film, such as Hannah Arendt and Martin Heidegger. Thoughts and reflections are conspicuous, yet there are few actionable deeds. Nathalie herself points out at one occasion: “it is impossible to reconcile thought and action”.

Hansen-Løve is only 35 years old and she has already directed several acclaimed films such as All is Forgiven and The Father of My Children. She is certain not to disappoint audiences with the quiet and powerful Things to Come.

Supported by very strong performances and a beautiful photography of Paris, the coast Brittany and the bucolic Vercors Mountains, Things to Come is a subtle commentary on the futility of philosophy, and the often weak intellectual fodder that sustains European literature and cinema.

Things to Come premiered at the 66th Berlinale (2016), when this piece was originally written. It was out in cinemas in August the same year. It’s on Mubi in October 2020.