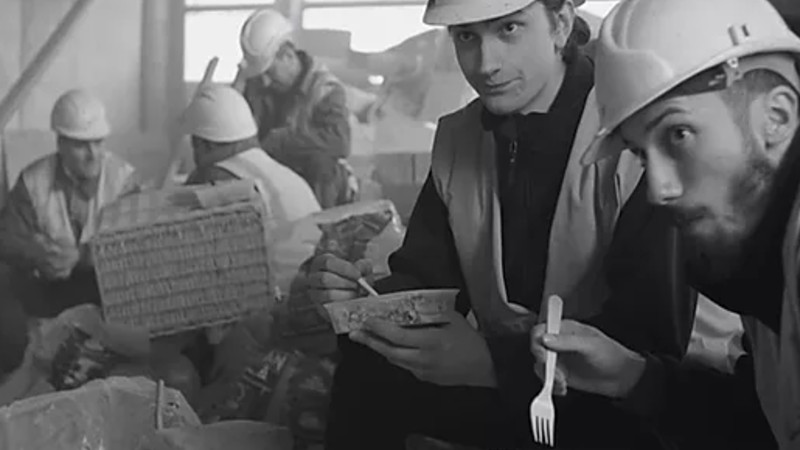

Mihai (Cristanel Hogas) is an immigrant. And as such he is divided between two nations. His beautiful wife and his young daughter dwell in Romania. Mihai is in London, where he toils as a construction worker, presumably in order to save money and provide a better future for his family. His relationship with his family is vibrant and colourful, while his life in the UK is sombre and colourless. This is emphasised by the photography, which switches from plush tones to black and white according to the geography and the protagonist’s state-of-mind.

The young Romanian gave up his own personal kingdom, complete with queen and little princess, in favour of a faraway and hardly hospitable Kingdom. He hasn’t seen his beloved ones in two years, he confides to a coworker. The United Kingdom is portrayed as a dark and divided nation. Immigrants are everywhere: there are Romanian and Bulgarian construction workers, and a Syrian refugee working in the local convenience store. Yet these people are not integrated into the heart of a nation that has become increasingly immigration-hostile and downright racist.

The action takes place shortly after the Brexit referendum. Enthusiastic Remainers are campaigning on the streets: “Not in Hackney, not in Brixton, not in our name, we want to Remain”. But the bigots are equally empowered, and the repression expresses itself in other shapes and forms. Mihai and other immigrants lose their job due to the prospect of leaving the EU, and Mihai has to work as a handyman in order to make ends meet. And he encounters violence on the streets: “Stop stealing our jobs and benefits, go back to your country”.

Memento Amare is a movie about wanting to move on, but being held back because of perverse circumstances. It is not a didactic and linear drama. The narrative is complex and multilayered. It zigzags back and forth: in time, between countries, between reality, allegory and imagination. Viewers are made to wear to shoes of a hard-working economic immigrant, and to experience his roller-coaster emotions and split allegiances.

Because the movie is not entirely chronological, there are hints of the disclosure in the very opening sequence. The outcome looks bleak yet inevitable. And it raises a number of questions: Could the psychological wounds of Brexit could stay open for decades? How will the “orphaned” generations react to having their king (and their kingdom) taken away from them? Is it possible that the young may seek justice with their hands? Is warring the only road towards redemption? One thing looks certain: solidarity has collapsed (perhaps to the point of no return), and the future is not bright.

You can watch Memento Amare at home on VoD.