Nic Sheff (Timothée Chalamet) is just 18 and he has has been missing for two days. New York Times writer David Sheff (Steve Carell) is frantically looking for his teenage son. He reappears with clear signs of drug use. He has just tried crystal meth for the first time, he claims. The reality, however, is much darker. We soon find out that Nic has been using various drugs (marijuana, cocaine, ecstasy). Plus, he has been a heavy crystal meth user for at least two months. Eventually, his brain to become rewired and the addiction takes over his life. Recovery at such stage is at single-digit figures, we learn.

Nic’s mother Vicki (who’s separated and living on the other coast of the US), David’s current wife Karen and their two younger children are all affected by Nic’s drug use. He spends time with both of his parents and also in rehab clinics in various parts of the country. At one point he disappears from one of the clinics and breaks into his own house in search of money to feed his drug use. He runs away with a girlfriend whom he introduced to crystal meth and who has also become addicted. He does not wish to be contacted. Until something happens.

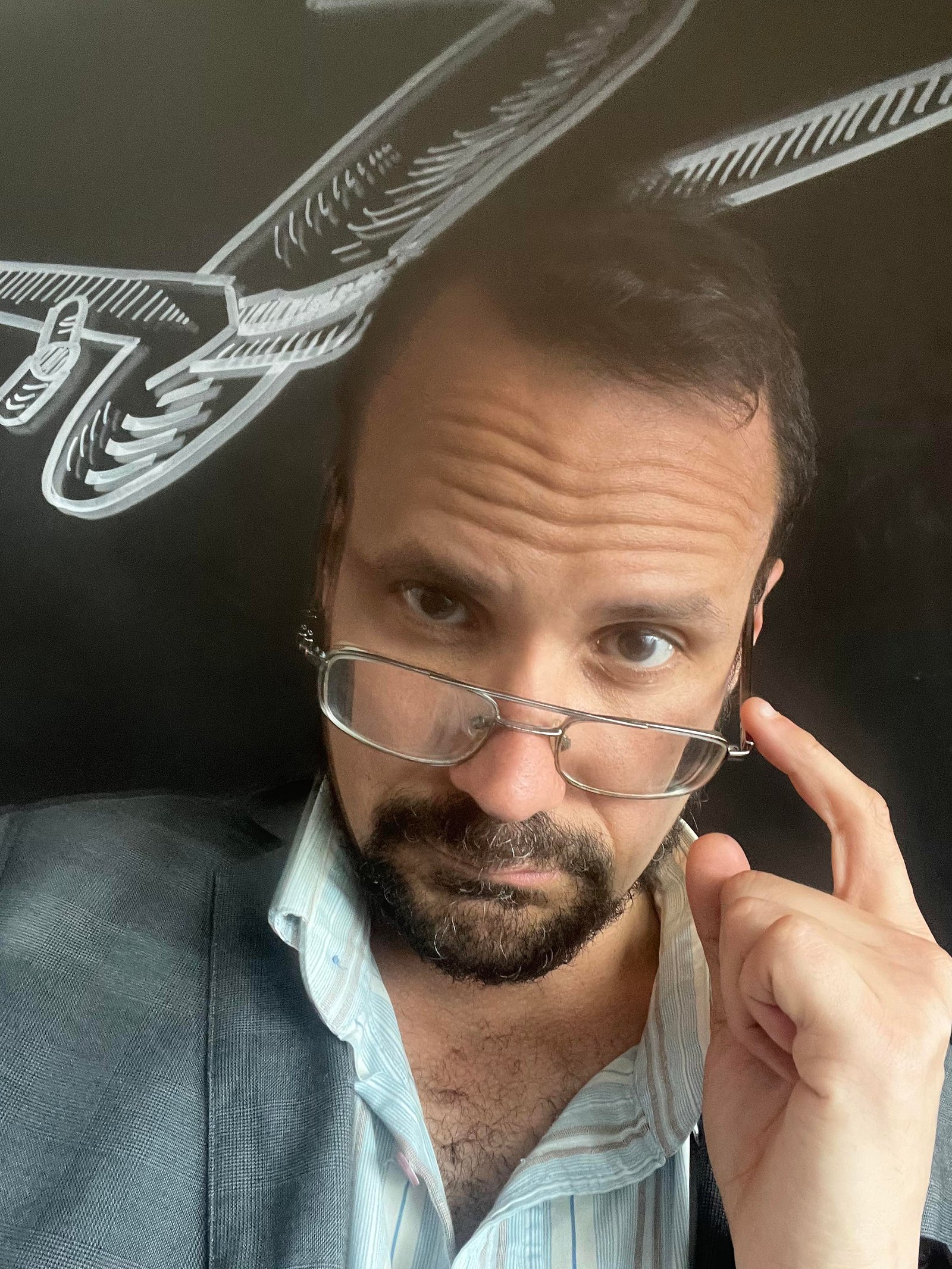

David’s pain and helplessness are extremely palpable. Carell does an outstanding job at conveying parental anguish and desperation. This is not the first time that the American actor interprets a father facing a major loss. In Richard Linklater’s Last Flag Flying (2018), his character deals with his son’s literal death. He’s equally convincing. His predicament here is no less tragic. Nic is not dead, but he’s gone in more ways than one. At times it looks like the only solution is to allow Nic to grapple with his tragedy on his own. It’s not an easy decision.

It is Chalamet, however, who delivers the strongest performance of the movie. The young French-American actor (who you will recognise from Luca Guadagnino’s 2017 Call Me By Your Name) depicts with accuracy his character’s stormy ride with plenty of relapses and a shocking ending with a double twist. We see a kind, sensitive and balanced Nic when he’s sober and a completely dysfunctional human being every time he falls into the drug pit. The euphoric highs are very credible, almost as if Chalamet had indeed injected crystal meth (I’m not suggesting he did, I’m just complimenting his acting!).

The Belgian director Felix Van Groeningen opts to show both sides of drug usage. The two strongest sequences of the movie complement each other. At one point, Nic and his girlfriend Julia inject crystal meth. It’s seemingly her first time, and his first time after being clean for a long break, so the high is particularly good. The sex that ensues is beautiful and passionate. On the other hand, we soon see Julia have an overdose and nearly die, in a very jarring, graphic and realistic sequence.

Beautiful Boy, however, is not a perfect movie. Firstly, its soundtrack is too pervasive, and also a little disjointed. You will listen to Jeff Buckley’s Song for the Siren, David Bowie’s Sound and Vision, Massive Attack’s Protection, John Lennon’s titular Beautiful Boy and almost the entire 10 minutes of Sigur Ros’s Svefn-g-Englar. These are all extremely powerful classics, and throwing them all together in the same movie can dilute their potential.

This is an important film with its heart at the right place. We learn that drug use is the number one death cause for Americans under 50. It’s very important that young people understand the consequences of crystal meth addiction, and how the use of lighter drugs can trampoline them into a downward spiral of heavier chemicals. But Beautiful Boy lacks the raw and unforgiving realism of Christiane F (Uli Edel, 1981): while some sequences are very convincing, other parts are laced with saccharine (particularly the musical bits). Overall, a good film with quite a few redundant elements

Beautiful Boy is out in cinemas across the UK from Friday, January 18th. On VoD on Monday, May 20th.