WARNING: THIS REVIEW MAY CONTAIN SPOILERS

Around half way through Mandy, the sophomore feature film from visionary Italian-Canadian director Panos Cosmatos, the reclusive Caruthers (Bill Duke) explains to vengeful Red Miller (Nicolas Cage) that the people he intends to hunt down and kill for brutally murdering his girlfriend have had their minds warped and twisted by some powerful LSD. There is no humanity in these sick souls. One might be thinking that as this scene plays out and Caruthers gives us the only tidbit of expedition the film offers that the ticket purchased from the kiosk to watch Mandy has also been laced with some bad acid.

Mandy exists as a headfuck, a hallucinatory trip, but it’s one worth taking and experiencing in all its lucid glory. The action takes place in 1983 in the Pacific Northwest of America that seems devoid of people, at least normal people. But we know this is no alternate reality, however much Mandy believes in the supernatural or the otherworldly. President Ronald Reagan appears on the radio rallying against drugs and pornography. If Mandy had been released at the time of Reagan, the moral majority would have flipped at its bent vision of religion and God. Still, the woods, mountains, and lakes are bathed in a fog of dreamy light and aura that offers a sense that weirdness is a norm in these parts.

Red and his girlfriend Mandy Bloom (a bewitching Andrea Riseborough) live in a rural retreat, a secluded cabin by Crystal Lake. Red works as a lumberjack whilst Mandy mostly hangs around the house drawing and reading wild novels of fantasy and as we later learn works in a local roadside store. Mandy is a doomed character. She seems to sense this and carries the knowledge that she will suffer an inevitable gruesome death with her. A scar under her eye hangs like a permanent streak from a lifetime of cried tears. A freakish cult, known as the Children of the New Dawn travels though the wilderness and when their alluring leader Jeremiah Sand (played to wicked and perverted perfection by Linus Roache) spots Mandy on the roadside he becomes instantly intrigued by her. He orders his minions to kidnap and bring her before him to be initiated within the cult as a servant and witness to his greatness.

Up to this point the film has unfolded in a slow and delicate pace. Conversations between characters have hung in the air and attributed nothing to the direction of the narrative accept to act as backdrops for the film’s genuinely gorgeous use of colour and cinematography. But the summoning of a weird convert of mutated bikers – think Hellraiser (Clive Barker, 1987) on wheels – by the cult’s henchmen to kidnap Mandy and dish out a beating to Red begins the film’s ascent towards its weirdo high. Mandy is brought before Jeremiah whom. He plays a folky recording of his own making to her Manson-esque fashion. It turns out Jeremiah was once a promising singer/songwriter. Anything sound familiar?

Although succumbing to the bad acid (and an odd wasp sting) that she is given by the converts, Mandy laughs in his face (and at his flaccid penis) and rejects his cult and his sexual advances. Jeremiah runs out of the room humiliated. Instead of further urging, the cult decide to burn Mandy alive and in front of a chained up Red. The scene is genuinely disturbing as the bagged up body of Mandy sways and writhes as the flames take hold as Red looks on. As the cult members leave Red is left to die chained up and gagged. Red frees himself by allowing the wire’s to cut into his wrists and once he crawls back to the house he stares at the television as a creepy commercial for Goblin Macaroni and Cheese plays. His life has fallen apart yet he still can’t pull away from a good commercial spot.

He then necks a bottle of vodka he finds in the bathroom and pours it over his wounds to stifle and cleanse the bleeding wounds. His soul however is shattered beyond repair.

This scene in the bathroom is a hard watch, though not for the reasons you might think. Shot from a single camera and a fixed wide shot, we watch in gruesome voyeuristic detail as Red moves from sobbing to shouting to screaming and back in only a matter of seconds. The scene is fraught with emotion, yet this scene is also played out with Cage wearing a tiger emblazoned t-shirt and a pair of soiled tighty whites. Any other actor might have found the nexus of emotion and seriousness in the characters situation to play it straight, but with Cage as Red it is played out with delirious lunacy.

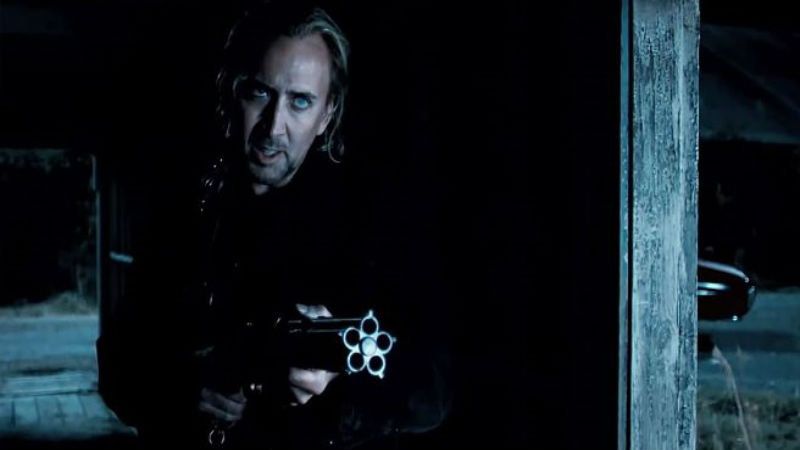

We enter in the half of the film in which Red seeks revenge on those that have wronged him. He locates an old friend, the aforementioned Caruthers, who loads him up with a crossbow and an assortment of swords and blades.

Unlike the ethereal first half of the film that moves at a snail’s pace, the last half shifts briskly and features some bloody horror tropes that are reminiscent of the Hellraiser franchise and Sam Raimi’s Evil Dead trilogy, especially the chainsaw dual between Red and a Children of the New Dawn thug which pulls heavily from Army of Darkness (1992) and of course Dennis Hopper’s maniac avenger in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 (Tobe Hooper, 1986). Red is victorious and his revenge against Jeremiah is complete when he tracks the leader down to his church and crushes his skull with his bare hands. With his mission over Red imagines his Mandy sitting beside him as he drives away from the horror. The maniacal grin on Red’s blood soaked face indicates that his mind has fully gone to the dogs.

Mandy is a blood soaked revenge caper, but its exquisite palette of colour and trippy use of lens flare takes it far beyond the b-movie shock horror it might have become. Lens flare, also known as panaflares refers to the process of aiming small LED lights into the barrel of the lens, The aesthetic is truly pleasing and immersive, conjuring a kind of hypnosis that draws the viewer in slowy and subtly. The trashing violence and destabilising, sometimes comedic performance from Cage shocks the viewer out of the fever dream for a moment, but the pauses of calm bring you back in easily.

Nonetheless, there is an otherworldly quality to the film that grounds it in the weird sci-fi novels that Mandy reads and the Heavy Metal genre and Dungeon and Dragons influences that bestow the film. Reviewers have commented on the idea that the film is akin to an Iron Maiden record sleeve coming to life. I’d like to picture something more modern such as King Gizzard and the Lizard Wizard’s recent concept records coming to life. King Crimson’s beautiful Starless opens the film as well as a title card of the last statement from death row inmate Douglas Roberts: “When I die, bury me deep, lay two speakers at my feet, put some headphones on my head and rock and roll me when I’m dead.”

The mutant biker gang might’ve added to this supernatural quality. When they are first summoned to do the dirty work of the cult they arrive in a red mist of dew and exhaust fumes. They appear to be from another dimension. When Red sets out on his killing spree he invades the gang’s domain. Except their domain is an abandoned house with discarded takeaway boxes and beer bottles littering the floors and tables. One gang member sits admiring the rhythms of seventies soft-core pornography. The bikers are clearly human, but so perverse and drug addled that the form no longer seems familiar. Their biker leathers seem fused to their skin. They are an odd bunch.

Speaking of odd, let’s take a moment to appreciate Nicolas Cage. His performance has been described as “wild” and “feral” and “overblown”. This is a fair assessment. Cage employs his most riotous tendencies here. We’ve seen only glimpses of this madness in films such as Drive Angry (Patrick Lussier, 2011), The Wicker Man (Neil Labute, 2006), and most recently in the comedy horror Mom and Dad (Brian taylor, 2017) and Paul Schrader’s gonzo Dog Eat Dog (2016), but in Mandy we see it come to fruition and it’s glorious. Cage is wrathful and yet incorporates intricate moments of subtle humour to elevate the insanity. Take for example the moment Red brutally dispatches a member of the mutant biker gang. He slashes away at his enemy and after coming out victorious, scoops a wad of cocaine up in his hand and gleefully snorts the lot. The performance is pure gonzo theatrics. Does it steal the film away from his co-stars and the importance of the narrative? Yes, no, and maybe.

It is also worth noting that Red actually has very few lines of dialogue. His conversations with Mandy mostly has him sleepily responding, whilst the conveying of emotion and his hack and slash revenge trip is mostly a bunch of hoots, groans, laughs, and cries. He’s given a few off kilter one-liners (“You ripped my favourite shirt!”) and any monologue (“Only one I believe”) is a stunted and jilted mess of incoherence.

There is another character in the film that you won’t find in the casting credits: the soundtrack. The last film score entry in composer Jóhann Jóhannsson’s incredible discography is a fitting, though sad end to a career that placed the soundtrack back in its rightful place as a vital component of a films aura. The music used in Mandy is a symphony of simmering ethereal synth and booming, decaying electric guitar. It literally shakes the screen. It’s a masterpiece that plays brilliantly by itself, yet take it away from the film and suddenly Mandy loses its unearthly quality. The soundtrack is a solid movement that pushes and prods the emotion within the film. If not accompanied by the film, it’s best experienced alone and in absolute darkness with a decent set of headphones.

Mandy is a very dirty and highly effective movie due to many factors: Cage’s performance, the outstanding soundtrack, the eeriness and dread of the first half, and the rage and madness of the second half. Yet as a whole it clearly belongs to director Panos Cosmatos. Cosmatos has created a vision that, while inspired by grimy VHS nastiness and late night sci-fi oddities, is truly singular. Cosmatos’s masterful approach aligns him with Kubrick and Lynch in delivering perfectly believable and fully realised worlds and characters that operate within their own laws of physics.

Mandy shows as part of the BFI London Film Festival taking place between October 10th and 21st – click here for our top 10 dirty picks from the event. It’s out in cinemas on Friday, October 12th. Out on DVD, Blu-ray and VoD on Monday, October 29th.