One year ago, on March 15th, about 100 film experts elected Todd Haynes’s Carol (2015) the greatest LGBT film of all times. The movie topped a list of 30 films that stretches back to the beginning of the last century and includes dirty pearls from all corners of the world. It was compiled in order to celebrate the 30th anniversary of the BFI Flare London Lesbian and Gay Film Festival last year. This year’s edition of the Festival is starting this week – just click here for more information.

I absolutely love Carol, and I have watched it twice with my eyes glued to the screen and my heart pounding with emotions. The movie is thoroughly delectable, and indeed an impeccable masterpiece. But something inside me also found this immaculacy a little awkward. How can a film be so perfect? So I decided to watch it yet again and concluded: Carol is a very clean film, and it does not fit in very well with our concept of a dirty movie.

This is by no means a bad achievement. It’s a natural step in the ascension of a previously marginalised culture within a capitalistic society. The incredibly beautiful Cate Blanchett’s impeccable clothes, hairdo and lifestyle are, in many ways, the epitome of the LGBT bourgeois ideal. The American conservative columnist Jonah Goldberg described this as “a concept subversive to both liberals and conservatives” in his LA Times column in 2010. But a lot has changed since, and LGBT culture has become so pervasive that it’s no longer subversive. In other words, Carol has pushed LGBT culture into the mainstream. Or the other way around (it pushed the mainstream into LGBT culture).

Despite the fact that Carol suffers with discrimination and sees her life turned upside down, she still comes across as enviable sample of a human being – from both an attitude and an aesthetical perspective. Plus she’s modelled after the great Hollywood actresses, a very conventional beauty standard. She therefore represents the replication and the perpetuation of long-established role models and ideals: very feminine, plush and preened. And this is not subversive. The same applies to her lover Therese, delivered by Rooney Mara.

The aspiration to live a high life in New York is also central to the movie. There is no doubt that the American metropolis is a mecca for gay people, and a hub for LGBT activism, but also a very mainstream one. In many ways, the shop where Therese works, the restaurants that the lovers visit and even their dwellings represent the concretisation of the American dream. A dream that has now become broader and more inclusive of various sexualities, but which remains extremely restrictive from an economic perspective. A dream that is either unattainable or undesired by the majority of LGBT people around the globe.

What’s happening to LGBT culture?

The bourgeiosation of LGBT culture of course doesn’t happen exclusively in cinema. Transgressive LGBT filmmaker Bruce LaBruce recently told DMovies in an interview: “I sense a certain moralism in the gay world, too. That’s because of the assimilation movement: gay marriage, kids, the military, even transsexuals colluding with the medical establishment. For me things haven’t changed much”. That’s not necessarily a bad trend, but we must be cautious of some possible negative consequences. Pinkwashing can be conveniently used as a lame excuse to cover up and even to justify certain atrocities, such as military action. I wouldn’t like to think that the commoditisation of gay culture cinema will culminate in gay soldiers killing “evil” Arabs and other obnoxious enemies.

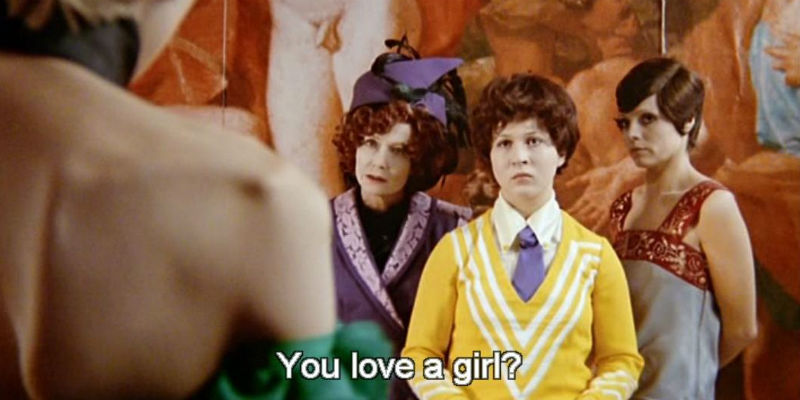

Let me emphasise once again that I do like Carol, and that I think it’s an urgent step in the history of LGBT activism. But I don’t think that it’s the greatest LGBT film of all times because it lacks subversive elements. It doesn’t have the controversial streak of Fassbinder, the provocative genius of John Waters or even the shocking antics of Todd Haynes himself in his early films. Carol is not Pink Flamingos (1972), the Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant (1974) and Poison (1991), respectively by the three aforementioned filmmakers.

A champion of change in cinema has to punch viewers in the face, as that’s the only way of cracking the pink glass ceiling. In Carol, Haynes instead gently caresses audiences. Fortunately, other films have previously shattered this glass ceiling. The repressive structure of discrimination just needs a gentle shake before it collapses – and this is what Carol and also this year’s the Best Picture Award winner Moonlight (by Barry Jenkins) are doing right now. The glass ceiling isn’t gone yet, but we are certainly moving in the right direction.