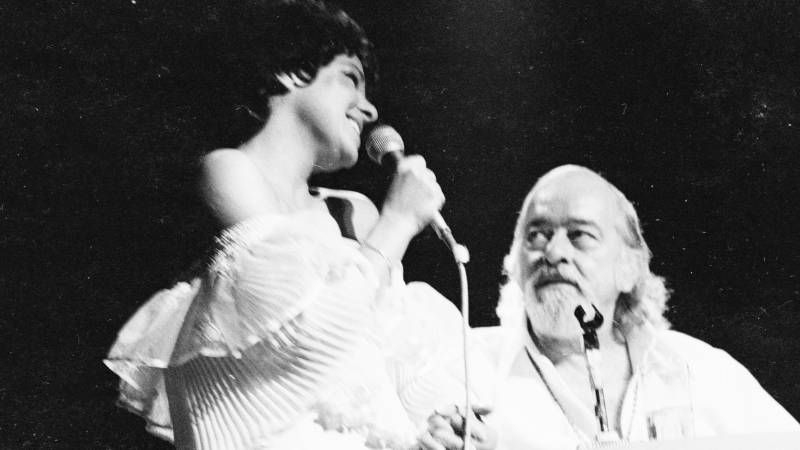

Miúcha, néée Heloísa Maria Buarque de Hollanda, was a singer of tremendous form and energy, boasting a free-spirited nature to her voice. But like a lot of women of her generation, it was her association to men that seemed to interest people more than her singular accomplishments, varied as they were. She was a sibling (Chico Buarque’s sister), a spouse (João Gilberto’s second wife), a collaborator (Antônio Carlos Jobim’s partner) and a disciple (Vinicius de Moraes’ pupil), but never a woman, an artist or a spokesperson. She was an attachment, rather than an entity. And this is something Miúcha, The Voice of Bossa Nova sets out to correct through a collection of personal letters, audio diaries and home movies.

One suspects that Miúcha might have handled things differently, but the 1970s was a male-dominated decade, and the fact that she sounded as vital as she did says a great deal about her character in a music industry that wasn’t as understanding as it might have been in later years. Feminism forms the film’s central dissertation, but Miúcha fans will be impressed by the throve of photos that are displayed onscreen, many of them taken in the studio. There, the singer can be caught in the middle of her process, unhindered by expectations or gender norms. There’s just her, a guitar player and a microphone.

The film also boasts an impressive watercolour sequence of a guitar floating away. Animated especially for the film, it encapsulates many of the documentary’s more pertinent themes: freedom, fantasy and a desire to let loose. It’s a beautifully produced sequence, yet the film never escapes the feeling that it could have been produced as a television programme. There’s nothing cinematic about the film: It’s centred on archival footage, voiceover work, and an absence of contemporary hook makes it an occasionally boring watch.

The soundtrack features a rousing version of ‘Samba de uma Nota Só (One Note Samba)’, demonstrating that bossa nova in its purest form is as exciting and as powerful as it must have sounded in the 1960s and 1970s when it was produced for the first time in Brazil. Music, like cinema, needs great resolve to realise it’s potential. Miucha’s documentary had some potential,but her voice was suffused with it.

The archived footage is fascinating, but the documentary does not entirely take off. Although the genre of bossa nova started off in Brazil, it later seeped into the rock lexis, and could be heard on some of The Beatles and The Doors most expressive work. Like many genres, bossa nova can be heard on modern day hip-hop, but you won’t find that information out in this documentary. It’s more the pity because when it works, the documentary really works, peeking right inside the eyes of the artist who spent her life (literally) fighting the man. “I was a lot less feminist than I should have been”, the artist says in a voiceover that’s laced in equal parts disappointment and acknowledgement.

Miúcha, The Voice of Bossa Nova premieres at the 10th Doc’n’ Roll Film Festival. Just click here for more information.