I hate violence in film. I hardly ever go to the cinema in order to see blood: I can count on one hand the violent movies I’ve seen in the past three decades. I particularly disliked Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction (1994), and laughing at violence. I have missed so many so-called classics!

I went to see Ultraviolence because it does not use violence as a means of entertainment. It does precisely the opposite: it raises awareness of very concrete violence and brutality. Ken Fero’s documentary follows the lives of the relatives of seven men who died while under police custody in the UK between 1995 and 2006: Christopher Alder, Brian Douglas, Jean Charles de Menezes, Paul Coker, Roger Sylvester, Harry Stanley and Nuur Saeed. These people seek explanations and redress, while struggling to understand and come to terms with the loss of their loved ones.

There is abundant violence in the film. Graphic and real violence, without music, without editing, without suspense. Death is neither staged nor reimagined. There is no glam and no redemption. We see people ignored and left to die, men treated worse than animals. A male dies on the floor of a police cell. Another one dies in front of several policemen, who chatter and laugh out loud as he takes his last breath.

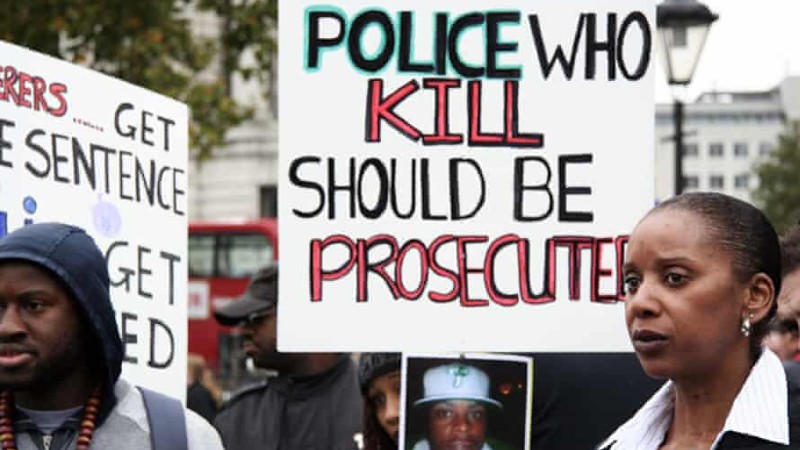

We also witness the struggle of their families as they try to establish the truth behind these deaths. There is frustration and anger as they comfort each other and campaign. They grow stronger as the movement gathers pace. The authorities consistently lie, procrastinate and even overturn convictions. Sadly and despite their perseverance, none of these families has received full redress or seen the murderers of their relatives behind bars.

The world has since changed: Black Lives Matter is now with us. Ken Fero’s documentary is a powerful reminder that that institutional racism is as ingrained in the UK’s social makeup as it is in the US, as we are forced to acknowledge that many of the lives lost to police violence in the film are indeed black.

The documentary goes further, perhaps a little too far. Police violence is linked with the Iraq War and colonialism in general. Janet Alder’s fight for justice for her brother merges with political activism as she joins George Galloway’s Respect Party. The individual struggles against police violence blend with to the collective struggle against the Iraq War. There are indeed connections to be made, however these could have been elucidated in a little more detail.

All in all, Fero crafted a powerful documentary reminding us that cinema isn’t mere escapism and entertainment. Cinema enables us to experience the pain of others.

Ultraviolence is out on BFI Player on Monday, July 5th.