No matter what you try and do, there will always be people who tell you it’s impossible. Tracy Edwards learns this the hard way. A school dropout working in a bar in Greece, she finds herself immersed in the world of sailing. But no male crew wants her. It’s the ’80s, women aren’t accepted into their macho crews. Nevertheless, she persists, working as a cook as they participate in a round-the-world sailing contest. Yet her dream is not in cooking, which by her admission, wasn’t very good. She wants to commandeer a ship herself, fighting against the odds to participate in the Whitbread Round the World Yacht Race with an all-female crew.

The result as narratively engrossing as it is genuinely uplifting, a mixture of the survival documentary and sporting inspiration tale. It shows the best way to prove naysayers wrong is through action. Edwards has quite the uphill task. Not only does she partake in a two hundred day race from the UK to Uruguay, Uruguay to Australia, Australia to New Zealand, New Zealand to the USA, and back to the UK again, but she must fight against a sexist culture that disbelieves her at every turn. It show that feminist progress is not something we should take for granted as an inevitability of progress but a constantly uphill battle built upon the back of gruelling labour.

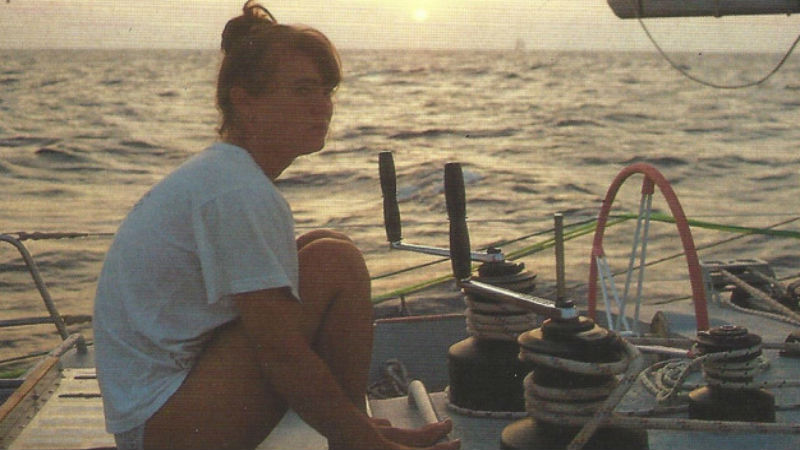

This is stressed by the enormity of the task Edwards has set herself. The dangers of the sea are apparent from Maiden’s first shot of roiling waves, accompanied by Edwards stating that, “The ocean’s always trying to kill you. It doesn’t take a break.” Whether it’s the freezing temperatures of the Southern Seas, or the turbulent, endlessly rocky seas around the Falklands, their Maiden boat is always up against the might of the deadly ocean. Footage shot from the ship itself during those times helps to illustrate this terrifying aspect. Edwards is completely humanised here, either from her own testimony or others, her headstrong devotion to success pushing her mind and body to the absolute extreme. A truly feminist icon (even if at the time she didn’t identify as one), Edwards’ ambition is simply incredible to witness.

Not only do these women prove themselves capable of voyaging, but after winning a couple of legs, are in with a real shot of claiming the top prize themselves. This gives Maiden a thrilling narrative sweep, the film’s keen editing of talking head recollections and news footage allowing us to be a part of the race itself. For those, such as myself, who don’t know the final result of the race, it brings to mind classic sports documentaries such as Hoop Dreams, her eventual success becoming so much more than just a question of sporting prowess.

More effort could’ve been expended into the nuts and bolts of sailing itself. While the story is terrifically motivating, it doesn’t serve as much of a blueprint for anyone wishing to copy Edwards. One also senses a stranger and more crazy story than the one we are presented with. Funding for the ship is provided by none other than King Hussein of Jordan, a bizarre fact of history that isn’t really expanded upon. Additionally, nearly everyone involved seems to be a hard drinker, landing at port and instantly guzzling a bottle of champagne. The highs must have been higher and the lows lower than any documentary could bring to life. If any documentary was ripe for a fictionalised retelling, Maiden has one of the most engaging storylines any adaptation screenwriter could hope for.

Maiden is out in cinemas across the UK on Friday, March 8th. On VoD Monday, September 30th.