It makes perfect sense that M.I.A wanted to be a documentarian. Like the role of a filmmaker, so much of her music is about giving voice to those who can’t speak for themselves. But in the process of telling stories, she eventually became one, her fame eclipsing the oppression of her own people.

Now a new documentary examines M.I.A.’s core belief: standing up for the oppressed peoples of her homeland. This has really been her mission all along. Matangi/Maya/M.I.A, created by her friend and fellow Central Saint Martin’s Alumni Steve Loveridge, really allows the rapper to speak for herself, showing that although she may have meandered along the way, her central philosophy has always remained on the same noble track.

Matangi/Maya/M.I.A is one of the most illuminating artist documentaries in recent years thanks to the copious amounts of documentary footage that M.I.A herself shot over the past twenty-two years. Although of varying visual quality, they give an authenticity often lacking in contemporary profiles, allowing us to really observe Mathangi “Maya” Arulpragasam as she slowly turns into superstar M.I.A. The early scenes, so evocative of London in the 1990s, are such absorbing naturalist documents that it doesn’t even seem to matter who the subject eventually became. But the girl named Matangi and nicknamed Maya eventually became M.I.A, thus befitting the three-layered title, and making for one of the best documentaries of the year.

A London-born woman of Sri Lankan origin, M.I.A. has always been caught between two worlds. She moved back to the island nation when she was six, but had to leave again at the age of 10 due to the ferocity of the civil war. Her own father was a key revolutionary figure in the fight for Tamil independence, which waged from 1983 to 2009, always giving her an interest in the plight of her people. The film does not take sides in the protracted civil war, instead using it as context to explain this singular musical personality.

This makes sense, as it is not a film about Tamil independence (a conflict one assumes needs a Ken Burn-type to make sense of) but about what it means to be an activist and a pop star at the same time. Maya starts the movie as a documentarian, travelling back to her home country in 2001 to film her family and the surrounding culture. The movie was never finished due to the dangers of the war and harassment by local men, but it taught her to bear witness, something that inevitably bled into her musical process.

Ditching the video cameras for drum machines, she saw music as the best way to illuminate the immigrant experience. Unafraid to embrace both the London and Tamil parts of her personality, M.I.A. becomes a representative of exiles everywhere. Her music combined the garage beats from her Hounslow council estate with an acute world music sensibility to become an almost instant sensation. Then thrust into a world of fame, M.I.A found herself the sole Tamil representative in a Western world. The rest plays like a checklist of her biggest controversies, with ample criticism from the Sri Lankan government (she should focus on her music) and the Western media (she should focus on her music) — both unaware that her music is her activism, and the two cannot be easily extricated from the other.

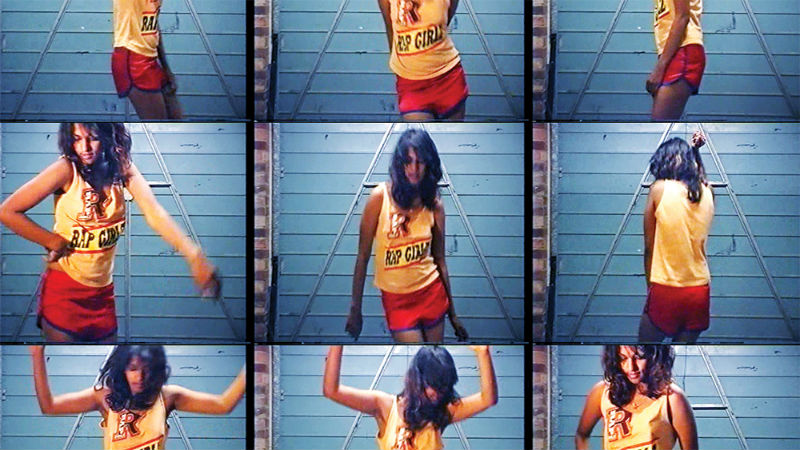

This is not your conventional music documentary. Little insight is given into how she composed her debut mixtape, how she met and collaborated with Diplo, or how she created her standout hit Paper Planes. Matangi/Maya/M.I.A. is far more interested in what the music stands for. Inspired by Madonna as a child, M.I.A. has the same ability to weaponise imagery in order to make defiant statements. Her iconic Born Free video depicted ginger kids being slaughtered over a thudding Suicide-sampling beat (an ironic allegory for the Tamil people). Later Bad Girls (directed by the equally incendiary Roman Gavras) protested the Saudi Arabian women’s driving ban with thrilling widescreen abandon. We see clips of these videos and others, going beyond conventional pop imagery of rappers on boats and girls in tight dresses to really spark dialogue about the world today. Her work is what truly remains: vital and provocative.

The main critique of M.I.A., coming out profiles such as the infamous 2010 New York Times Magazine article entitled “M.I.A.’s Agitprop Pop”, was that she was appropriating the language of resistance to sell records. This may be true, and her approach may come off as a little crass, but there’s no doubting her heart is in the right place. Matangi/Maya/M.I.A finally allows the authentic M.I.A to speak for herself. Now is the time to listen.

Maya Matangi M.I.A. is out in UK cinemas on Friday, September 21st. It’s out on VoD on Monday, December 10th.