In the twin worlds of animation and movies, Japanese director Isao Takahata – who died yesterday aged 82 and whose death was announced earlier today by Studio Ghibli – was one of a kind. In 1985, following the success of Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984) which Isao Takahata produced and Hayao Miyazaki directed, the two men founded the animation company Studio Ghibli. People who know Ghibli tend to know the Miyazaki films, blockbusters in their home territory of Japan and big successes among family, animation and foreign language audiences internationally. Very fine films they are too. But Takahata is a slightly different kettle of fish.

Where Miyazaki, at least until he reached old age and started making noises about retiring, turned around a new film about every two years or so and these tended to be hits, Takahata often took twice as long and the resultant films were much less viable commercial propositions. This is the man who, for example, early in Ghibli’s history made a live action documentary about canals (The Story of Yanagawa’s Canals/1987), something about which he was clearly passionate but hardly the sort of blockbuster follow up to Nausicaä that would impress the bean counters.

.

Not just another animated face

His next Ghibli film, the profoundly affecting Grave Of The Fireflies (1988), was a long way from traditional children’s animated fare being the story about a young boy and his much smaller sister orphaned during WW2 and their struggle to survive in an abandoned bomb shelter on a riverbank. It’s harrowing, tear-jerking and stunning.

Other films included Only Yesterday (1991, pictured above), in which a 27-year-old office girl rediscovers herself upon moving to the countryside. It’s peppered with flashbacks. The resultant film was considered so inherently Japanese by the Studio that for over two decades they refused to dub Only Yesterday into English, believing the task an impossibility. (Ironically, the excellent dub the Studio was eventually talked into a few years ago is in this writer’s opinion one of the few instances where for English-speaking audiences the dubbed version of a foreign animated film surpasses the original subtitled one).

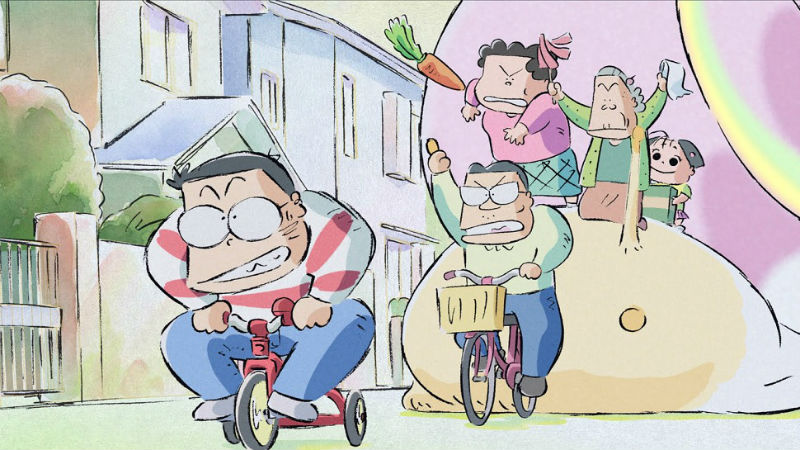

His 1999 feature My Neighbours The Yamadas (pictured below) again broke the Ghibli mould in terms both of unfamiliar production techniques and visual style. Takahata wanted to create something akin to a newspaper strip cartoon wherein characters are loosely delineated by lines while the odd bit of pastel shading replaces the fully coloured-in look (the aesthetic historically popularised and locked in to the popular concept of what an animated film should look like by Disney’s industrialisation of the medium).

Takahata was determined to utilise computers – but not in the way that everybody else in animation did which was to create more immersive, three dimensional looking worlds and characters. He was after a completely different quality. If his approach indicated a purity of artistry, it made little economic sense. The Studio swiftly moved on to a more successful Miyazaki project (Spirited Away/2001) and Takahata didn’t work on another project for years. But he had introduced computers into Ghibli’s production process as a by-product of his artistic obsessions.

.

A life extraordinary

The sheer quality of the director’s films inevitably had its admirers. In 2005, a Nippon Television Network executive approached Ghibli with the money to fund another Takahata offering so that he could go to his grave knowing he’d done so. Given a completely free rein, Takahata spent five years in discussion with a young Ghibli producer about a vague project which looked like it might never materialise. Eventually, he was talked into directing his own conception of an adaptation of the Japanese folk tale The Tale Of The Princess Kaguya (pictured below), but as production dragged on, dogged by Takahata’s perfectionist approach, it looked for a while like it might never reach completion. Takahata was dissatisfied with one element here and tinkered with another one there. Those who had to work with him must have been tearing their hair out. The film eventually appeared in 2014, a remarkably rich and strange work which no-one would make if their only intention was box office returns. Widespread international acclaim and an Oscar nomination followed.

Isao Takahata was a cinematic maverick whose refusal to play by the industry’s rules could easily have destroyed him. Instead, thanks in no small part to his association with Miyazaki and the latter’s considerable faith in him, Takahata directed a small number of truly remarkable films. We should be thankful his career went the way it did: he’s a director whose idiosyncratic vision overcame impossible obstacles to leave an indelible impression. His passing is a great loss which will be felt both by those at the Studio he co-founded and in the wider world of international film culture.