The year is 1971, the month is November and the city is Leningrad. The urban landscape is covered in snow and the air is foggy. The mood of people is equally sullen and morose. After experiencing a period of relative freedom in the 1960s, the Soviet Union is once again gripped by censorship. It’s almost as if Stalin had made a return. The climate (in both the denotative and the connotative senses) is nasty. Plus, a sense of economic and political gloom prevails. Publishers seek “positive” writers who will convey a sense of hope and lift the spirits of the populace. The entire film takes place during a period of seven days.

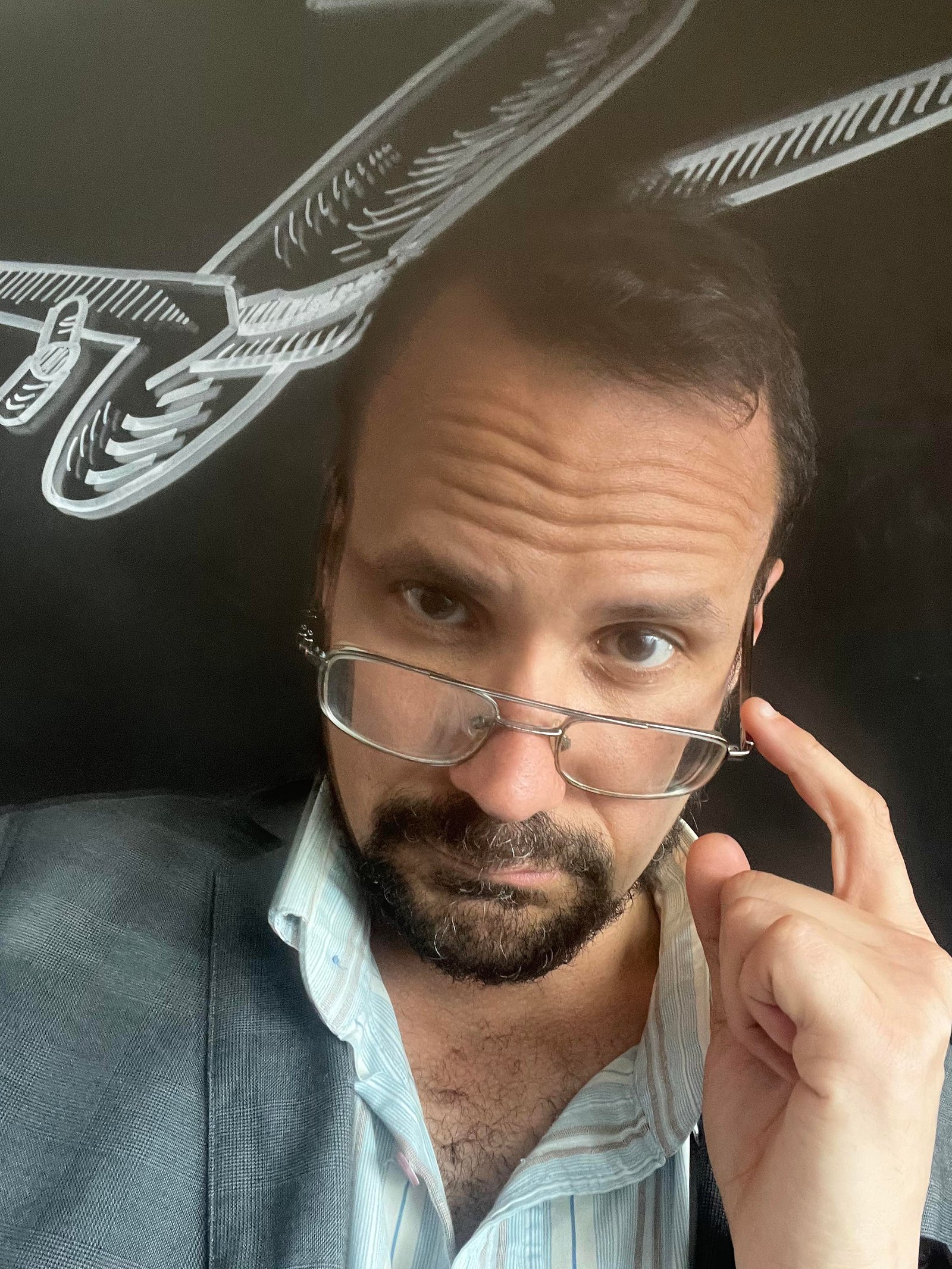

Russian-Armenian journalist Alexei Dovlatov (played by the bulky Serbian heartthrob Milan Maric) does not wish to conform to the newly established orthodoxy. His writings are too subversive for the official media, and he is consistently denied membership by the ultra cliquey Writers’ Union. He endeavours to capture social reality: he visits and talks to shipyard builders and metro construction workers. He does not wish to leave the Soviet Union. He wants to stay and lead a normal life with his wife Lena (Elena Sujecka) and their daughter Katya.

Dovlatov’s ironic and transgressive writings were prohibited under Brezhnev, and he eventually migrated to the US, shortly after his friend Iosif Brodsky (also portrayed in the movie). Both men would eventually become recognised as some of the most influential Russian writers of the 20th century, and they die while living in New York – the film explains in writing at the end.

Dovlatov blends tragic events that took place during that week in November – such as the attempted suicide of a co-worker and the accidental death of a painter arrested for smuggling – with the oneiric (we see Dovlatov’s fears beautifully portrayed in two dream sequences). Polish DOP Lukask Zal (of Paweł Pawlikowski’s Ida, 2013) delivers a visually compelling movie, with a reality as murky and misty as Dovlatov’s imagination. The images of the majestic Saint Petersburg (then Leningrad) are enthralling (not too difficult, considering the city in question). Dovlatov, however, is artistically inferior to the black and white Polish film from five years ago. It’s far less audacious and inventive.

In case you have never heard of the Russian writer Sergei Dovlatov or are only very vaguely familiar with his work (I belong to the latter category), then you might find his biopic a little esoteric and overwhelming. References are so abundant and intertextuality so prominent that people lacking the specific cultural capital might not be able to engage with the film thoroughly. Gogol, Dostoyevski, Tolstoy, Pushkin, Chekhov, Solzhhenitsyn, Nabokov and many more are repeatedly referenced. Non-Soviet artists of all sorts and eras such as Pollock, Munch, Hemingway and Sophocles are also discussed. The namedropping is so intense that it’s difficult not to keep track of it.

All in all, this is a conventional biopic with an elegant photography and plenty of treats for fans of Russian literature, but nothing beyond this. It is unlikely to convert new fans. I would hazard a guess that the Russian director Aleksei German, who won the Silver Bear for Outstanding Artistic Contribution just three years ago with Under Electric Clouds, will neither repeat nor excel his achievement.

Dovlatov showed at the 68th Berlin International Film Festiva, when this piece was originally written. It premieres in the UK as part of the BFI London Film Festival taking place between October 10th and 21st.