In the past week or so, went to see two documentaries part of the East End Film Festival (EEFF), which ends tomorrow. They were Timothy George Kelly’s Brexitannia and Damani Baker’s The House on Coco Road, both made this year. Both were shown at the Rio Cinema in Dalston, both were followed by a QA with their respective directors. The two films couldn’t be more different, yet there was something far more important about the overall experience.

Brexitannia, shown on Saturday evening, was a long black and white exposition of the different views of several people who voted in the EU referendum. I expected the documentary to show both sides of the argument and although a few among those selected had voted for remaining in the European Union, most of the participants espoused a Brexit point-of-view. There is nothing wrong with that. As a metropolitan, immigrant, middle-class, middle-aged, university educated, Londoner, I don’t need to be listening to the views of people like me. Part of the exercise was, indeed, to get a little more understanding into the views of those who think differently from me.

Break-away Britain

In the cinema, there were ‘eccentric’, mainly working-class people, generally being confronted with the dilapidated and ugly part of the country on the silver screen. The interviewees within the film were mostly in scrublands, council estates, broken down factories or a workingman’s club in areas such as the North-East of England, Northern Ireland, Clapton in Essex or the South West, describing their fears and what made them vote Brexit.

The documentary was divided in two parts. We knew this was so because we were helpfully given the title “Part One: The People”, before the participants started talking. It was all vaguely interesting and amusing. The audience sometimes laughed out loud at some of the views held by this strange bunch, living somewhere outside the M25.

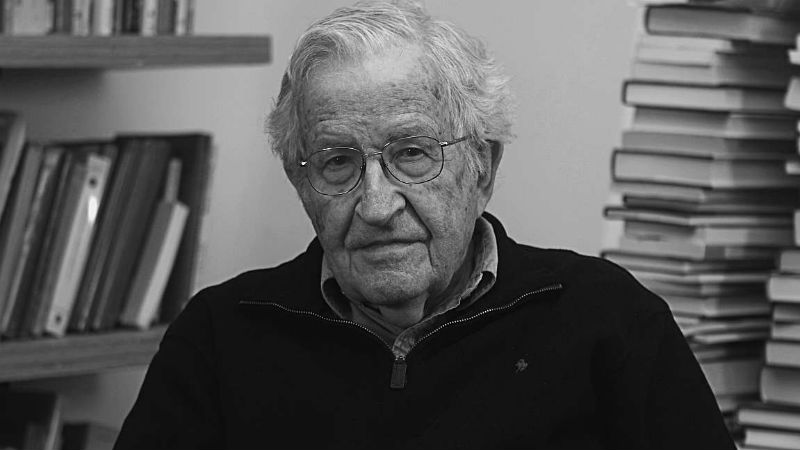

But there came a point when I was positively looking forward to what else we were going to get after ‘the people’, hoping that there would not be too much of it and that it was not going to go on for too long. Indeed, after “Part One: The People”, came “Part Two: The Experts. A group of half a dozen or so prominent individuals chosen to give their educated views on Brexit – one of them being Noam Chomsky (pictured below).

A monolithic view

I did not dislike the doc at all. I went imagining I was going to enjoy it and was prepared to leave thinking it was a bit long and rather forgettable, but ok. The problem was the discussion afterwards. Let’s be explicit, I was not the only metropolitan person in the audience; I was one of many and, mostly white, new-Dalstonite types. If there was a difference between the rest of the audience and me, it was that I was perhaps slightly older and perhaps more conservative in my dressing.

As well as the director, there were a few of the film’s ‘experts’ on the panel, lavishing praises on him, telling him what a sensitive documentary it was, how he had let ‘people’s feelings come through’. Except that… the audience had been laughing at the characters portrayed, just as much as the film’s subjects would probably have been jeering at us, if someone had made a film about ‘London Metropolitans’ and showed it at some workingman’s club in the middle of one of County Durham’s defunct mining villages.

A member of the audience even asked the director “what do you think about the audience laughing during the showing”, to which he replied: “they were uncomfortable with the views exposed”. Rubbish!! We were laughing because, despite his attempts, Timothy George Kelly was unable to break the ‘us vs them’ barrier. Other questions followed such as “where were the black people?” (few) “Black people will mainly talk about colour” Kelly replied, immediately realising his gaffe. “What about the middle-class? Some of them also voted Brexit?”, asked another. “Oh, middle-class views are boring, they know how to express themselves” and so he went on, dismissing his audience.

Kelly, unable to move away from portraying his subjects like animals in a zoo, was now pontificating that we, the pro-European Metropolitans, had to accept the Brexiteers’ views, following the same line of argument used by the mainstream media: any debate or dissent is anti-democratic and ‘condescending’. Brexitannia did absolutely nothing to move us beyond the current division we live in, or to elucidate in any way what is a very complex subject.

United in our New World roots

The next morning I went to see Damani Baker’s The House on Coco Road. On my way to the Rio, I was already wondering what type of people I would encounter at the cinema. Some Caribbeans, since the film was (somewhat) about the Island of Grenada, a few left-wing romantics like me, and… quite a few empty seats.

I arrived to see a huge queue outside of people still looking for tickets. All mainly Black and almost all Grenadians. I sat at the back of the circle next to a lady my age and we started talking, why was I there? What relationship did I have with Grenada? I told her about my Latin American background and our mutual historical links, my interest in the Caribbean, etc.

Having now moved away from the area, she told me about being a child on Sandringham Road, the Hackney ‘frontline’, before Dalston `viralised’ and about coming as a child to matinees at the Rio. We talked about Caribbean immigration, how many of the older population had `returned home`, and how others, including herself, had moved out because of the bad reputation the area had in the ’80s and ’90s.

The documentary started late, whilst the staff tried to accommodate the, mostly female, crowd. Meanwhile, we had some footage of the speeches of Maurice Bishop, the revolutionary Prime Minister of Grenada who was murdered in 1983, just before Ronald Reagan sent in the armed forces to the island. It was not really about Grenada or Bishop, but about the director’s mother’s: a sensitive and respectful rendition of the life of a Black woman and activist, in his words, about one of many “extraordinary women…(who live their lives) in the face of tremendous obstacles”.

Although centred on their family’s experience of moving to Grenada in 1983, after Maurice Bishop, leader of the People’s Revolution became Prime Minister, the story starts much earlier, with Baker’s grandparents leaving Louisiana for California as part of the mass migration to the North, when approximately five million Black Americans left the racist South.

Baker’s mother, Fannie Haughton, was the first woman in her family to go to university, UCLA in fact, where she met and became friends with the black feminist activist Angela Davies, who also features in the documentary. House on Coco Road is an intelligent and surprising documentary which teaches us about some extremely significant and yet relatively unknown events, which took place in the 20th century. In a personal way, it sheds light part on the history of the American continent, of Black people in general, decolonialisation, as well as left-wing and feminist politics. It is a tribute not only to his mother, but to the power of idealism, the need for utopian dreams to make our lives meaningful and the importance of fighting for what we believe in.

Two films, multiple identities

In their own ways, both documentaries, discussed an important contemporary topic: identity. While Timothy Kelly’s documentary Brexitannia is about ‘them’ shown to ‘us’, without providing a tool for us to break our own bubbles and reach the ‘other’, Baker offered us a film about nothing else but himself – though by doing so, it involves us.

Especially the Grenadian audience, because it was also a film about how what happened in that tiny little island on the edge of the Caribbean had an incredible impact on his life. In other words, Baker’s documentary was able to build bridges and make bonds.

Indie cinema needs your help

As part of the EEFF, both documentaries brought very different audiences to the Rio, a popular, and still independent local cinema. The EEFF and the Rio cinema are here in order to provide something distinct from the mainstay of commercial houses like Vue. The Rio (pictured above) has managed, so far, to survive. It is about to launch a crowdfunding campaign for its much-needed refurbishing and build a second screen, they say they will need £150,000. You too can become part of the RIOgeneration campaign by clicking here.

Let’s hope it is successful so that it continues to attract different crowds for the variety of films and film festivals it screens, because the London cinema scene very much needs places that are open to diversity.