A setup. A restraint. A promise. That’s all we’ve got to know to embark on Fritz Lang’s Destiny, which is returning now to British cinemas. Premiered in last year’s Berlinale, this restored version updates the 1921 German production’s color and soundtrack. Its core, however, still shivers with the fears of the Weimar Republic. It also reflects some of modern angst, which we experience nowadays.

Despite that, Lang’s production is, first and foremost, an expressionistic fairy tale with a healthy dose of ambition. Starting off with the introductory titles “some place, some time”, we’re presented to two unnamed lovers. They give a ride to a mysterious man in black into town.

At the local joint, the three of them reunite and a little bit of supernatural activity comes into play. The lady goes to the toilet and returns to find that both of them are missing. The tragic reality suddenly surfaces: that tall dark stranger was the Grim Reaper and her lover’s now dead. Some suicidal thoughts later, the lady begs Death for his return and he appeases her with a bet. He shows her three lives in danger and, should she save one of them, he’ll grant her wish.

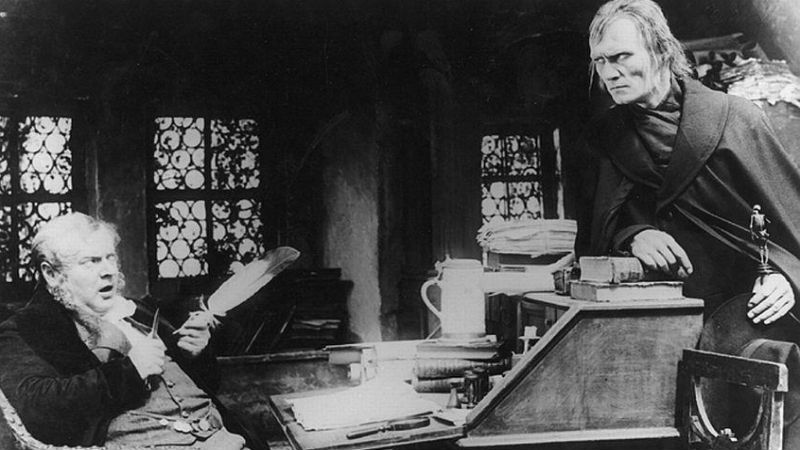

The prologue acts as a frame story for three fables set in, sequentially: an Arab country, Italy and China. They all involve doomed couples and, though simplistic, come in beautifully-rendered Expressionist flair. Their common denominator is even reinforced by the same actors (Lil Dagover, Walter Janssen and Bernhard Goetzke) appearing in all stories. That ends up being the film’s most compelling quality.

The turbulent post-WWI Germany was, not unlike today, ripe for the us vs. them narrative in politics. Considering that, it speaks volumes that Lang wanted his meditation on death to show how mortality unites mankind. By setting his picture in three very different countries and times, he brings our shared fear to the forefront. Love and death, the two big motifs in the film, play out the same for Germans, as well as Arabs, Italians and the Chinese. His beliefs (and Jewish heritage) caused him to flee the country as the Nazi rose to power.

It also shouldn’t be missed by the attentive viewer the critic the filmmaker makes of systems of power. In the fables, the tragedies that befalls our characters always come from a powerful source, usually corrupt to some degree. In the first story, we see the dangers of power becoming entwined with religious fundamentalism (sounds familiar?). In the second, we’re spectators to the good old jealous ruler. And in the third, a sheer demonstration of totalitarian force goes awry. In Lang’s legendarium, death comes to us, but we, as a society, do provoke it with a passion.

Despite the gloomy subject, the tone of Destiny is strangely upbeat, with a brave heroine (Dagover) echoing the wishes of the audience. The most obvious counterpoint to that is Death itself, portrayed with perfection by Goetzke. Grim Reaper is as tired as any worker stuck in London traffic at rush hour, and you can feel his misery. When confronted with the affection, his response is a void look on his face – the modern of expression of indifference we all recognise. It’s as if his heart was screaming: “Nothing matters at all!!!”.

On the other hand, Destiny mattered a lot, particularly to Lang’s career . It was his first international hit and granted him the necessary status to make Metropolis (1927) and M (1931) afterwards. It reportedly inspired Luis Bunuel to make films and once impressed Alfred Hitchcock. Ingmar Bergman also seems to have taken cues from the Death character in The Seventh Seal (1957). But, underneath its artistic importance, there lies a film that dares to tell us that, even in the most difficult times, we all bleed and are faced with mortality in very similar ways.

Der Müde Tod in being released in selected cinemas across the UK and Ireland on June 9th, and it’s also available on digital HD on the same date.

Click here for another film classic taking place during the Weimar Republic, and also dealing with the subject of death – which is also showing in cinemas.