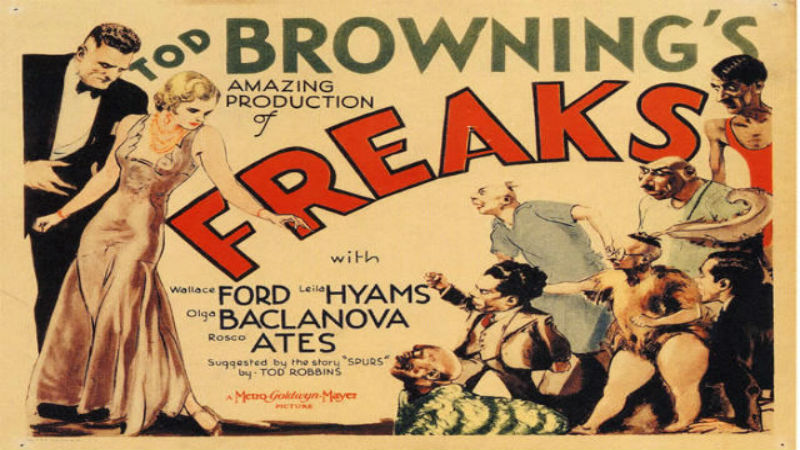

While the concept of diversity is a modern concoction intimately connected to the Civil Rights Movement in the US, LGBT rights activism and the New Left agenda of the 1970s in many countries, the notion that the should embrace the different is, of course, much older. Tod Browning’s Freaks, which was made nearly a century ago in 1932, is an early champion of diversity, despite the fact that the American filmmaker himself never knew the concept. Remarkably, Freaks remains the most audacious and thought-provoking statement for diversity in film in the relatively short history of cinema. Diversity includes race, religion, gender, class and also disability, the latter being the subject of the film in question.

In Freaks, eponymous characters were played by people who worked as carnival sideshow performers and had real deformities and medical conditions. This includes the Bearded Lady, the Stork Woman, the Half-Boy Johnny Eck, the conjoined twins Daisy and Violet, the Human Torso, the Armless Wonder as well as various sufferers of the Virchow-Seckel Syndrome (which gives humans a bird-like appearance with a narrow face and pointy nose). The central plot is around an able-bodied trapeze artist called Cleopatra, who deduces and marries the sideshow midget Hans upon finding out about his large inheritance. She attempts to persuade the circus strongman Hercules to kill Hans so that both can have his wealth.

The able-bodied woman is the wholy corrupt and ugly character in Freaks, while the “freaks” are profoundly integral and beautiful. The message within the film is as bright as daylight: ugly is beautiful, and you should never judge people by their appearance. And ultimately: the freakier your body, the bigger your heart.

People reject the different

Despite its very noble intentions, the movie backfired. Society just wasn’t ready for such candidness. Society didn’t want diversity. As a result, the film was heavily edited down to just 62 minutes (from the original 98 minutes). Still, viewers convulsed, vomited and left the cinema in droves. And a woman allegedly had a miscarriage while watching it.

So, how would audiences react to Freaks if it was made now? We would neither throw up nor lose an unborn baby. We have now adapted to the most absurd shapes and forms in cinema, as grotesque and repulsive as one can imagine, from frothing aliens to roaring zombies. Yet most of us would feel extremely uncomfortable with the realism of the film, and many people would indeed walk out of the movie theatre. We have grown accustomed to a visually sanitised cinema with unachievable beauty standards, plus a tedious celebrity culture consistently imposed on us. Most of us want people to look pretty on the silver screen. We are happy to see freaky monsters created with the help of special effects and computer animation, but we decry real and graphic images of the imperfect human body. We often describe those as either “unnecessary” or “sheer bad taste”.

While many of us have embraced diversity and become more used to nudity in cinema, we’ve also learnt to sanitise the different so that it becomes more palatable. No film has ever portrayed people with deformities in a way as candid and straightforward and with a message of inclusion as crystal-clear as Freaks.

The controversy surrounding Freaks helped to trigger the Motion Picture Production Code, which vouched for “decency” in American cinema for many decades to come. The moral guidelines of the Code may have been removed since, but its impact on the industry still lingers, as the market naturally rejects anything that’s too “crude” with the human body. The commercial failure of David Cronenberg’s Crash is a shining testament of our inability to embrace the imperfect human body.

Television versus cinema

To be fair, the UK government and British television have gone to great lengths in order to make people more comfortable with the least usual aspects of our pathology. Channel 4’s Embarrassing Bodies certainly does that, as do most of the TV shows featuring the charismatic Adam Pearson – who has neurofibromatosis and has been involved in outreach programmes to prevent bullying associated with deformities. Under New Labour, I also remember seeing street adverts showing people with facial disfigurement and urging the population to engage with them – sadly those have now vanished.

Strangely, remarkably little has been done in British cinema. London does have its annual Disability Film Festival, yet more mainstream cinema practices either reject or sanitise people with disabilities. There has never been a film like Freaks in this country and perhaps there will never be. Maybe we simply don’t want to see disabled and disfigured people exactly as they are.

In a nutshell, I still think that Americans and Brits alike are not comfortable with the fact that the human body isn’t always pretty and proportionate. Grotesque doesn’t mean unnatural. Grotesque IS natural. Once we are sophisticated enough to understand this, then perhaps we’ll be prepared to embrace diversity more wholeheartedly.