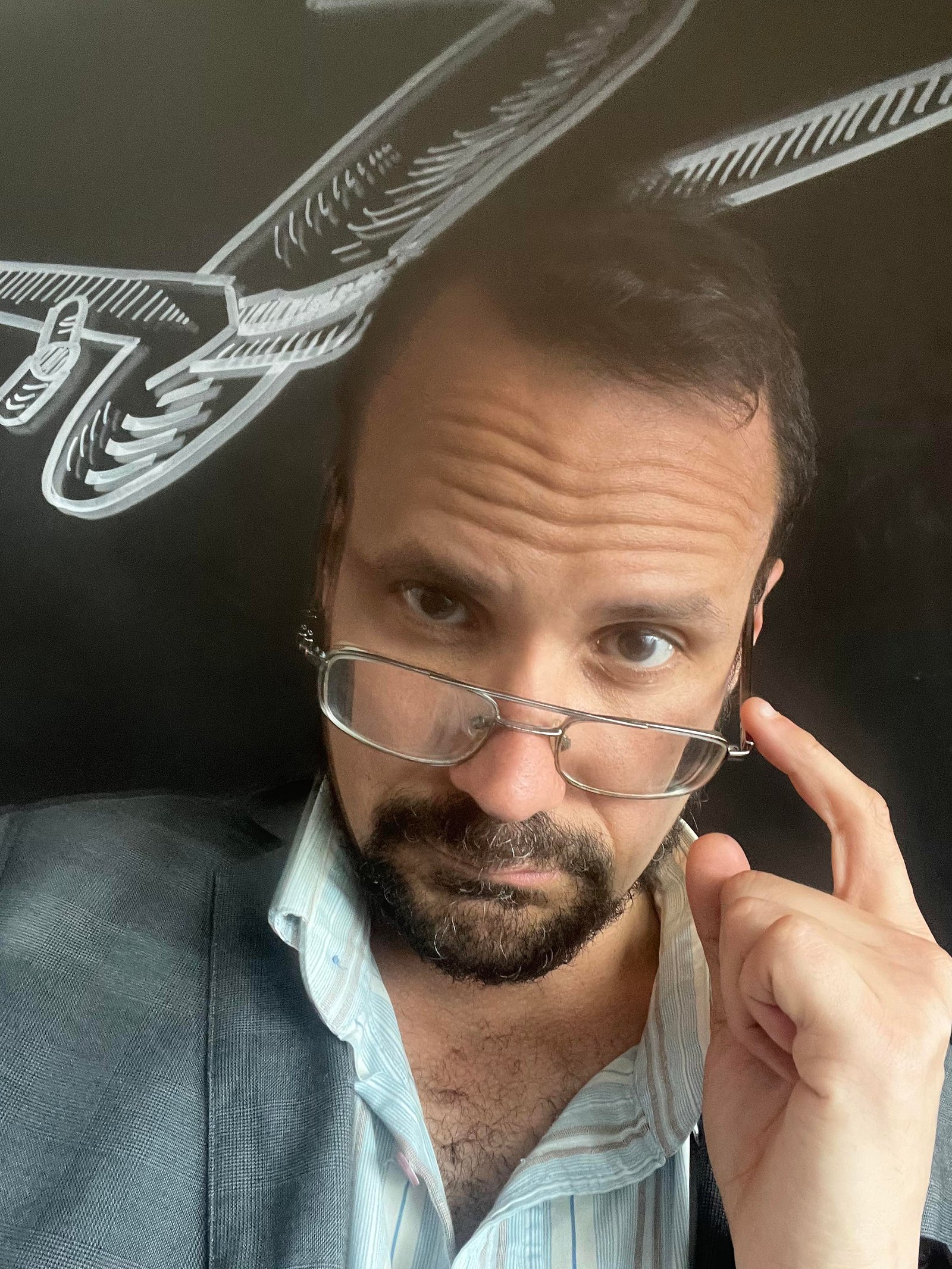

Set in the 1960s, Mahana presents Temuera Morrison as the ruthless Maori patriarch Tamahina (pictured above) of the Mahana family somewhere in the countryside of New Zealand – the film director himself is of Maori ancestry. Tamahina Mahana has firm control over his children, grandchildren and in-laws, often exercising his power through threats, verbal and physical abuse. He claims that they own him everything, and he often boasts his accomplishments in firmly establishing his well-to-do family of sheep shearers. Most in his relatives live in fear of the patriarch, and they prefer to shy away from confrontation. They are as passive and sheepish as the animals that they shear.

Grandfather Tamihana Mahana does not tolerate any affronts, and all members must obey and agree with him at all occasions. He promptly beats up his grandchild Simeon (Akuhata Keefe) because he challenged his grandfather’s knowledge that there are no films about religion. Simeon’s father Joshua Mahana (Regan Taylor, who looks like a Maori George Clooney) steps him and beats his own father in defence of his son. As a consequence, grandfather evicts Joshua, his wife and children (including Simeon) from his household and disinherits them.

It is then revealed that grandfather Tamahina obtained his wealth through violence and deceit. He raped his wife Ramona (Nancy Brunning) when she was engaged to a man in another family, and he does it in her own house. She became pregnant and therefore Tamihana Mahana gained control over the property and the estate that he now owns.

Grandfather Tamihana’s behaviour is similar to European colonisers in New Zealand and elsewhere: they robbed the land from its owners through deceit, raped the local women and perpetuated their power through brutal and unrelenting oppression. Simeon himself reminds a judge during a school visit to a court that the Maori could never defend themselves properly, as they are not even allowed to use their language in the precinct.

The film also delves with female powerlessness and the endurance of love. Ramona explains that she never had any opportunity to break out of the violence imposed on her, and yet she never stopped loving the man to whom she was originally engaged. Her immortal passion is tantamount to the feeling that Maoris have towards their land, and how they have consistently resisted the influence from their colonisers, or at times integrated it with their culture.

The acting in Tamahori’s film is strong and convincing, the script is gripping and the photography is mostly bright, colourful and vibrant. A sequence where grandmother Ramona sings in Maori surrounded by bees in an apiary beautifully epitomises theanguish and pain of being trapped by a man whom she hates.

On the surface. Mahana is a tearjerker and an aesthetically conservative film, with little difference from most mainstream movies. These inflammatory allegories of colonialism and male dominance, however, make the movie a powerful and universal political statement.

Mahana debuted on February 13th at the 66th Berlinale. DMovies is live in Berlin at the event sweeping the dirt from under the red carpet.